We are thrilled to welcome our new Assistant Professor of Nordic Studies, Dr. Tim Frandy, to the University of British Columbia, to unceded Musqueam lands, to the Faculty of Arts, and to the Department of Central, Eastern and Northern European Studies. Their research and teaching will enrich students’ knowledge of Nordic and Arctic history, literature, art, languages, and society from the perspective of Sámi and other Indigenous communities. Dr. Frandy joins us as part of the Climate Emergency cluster in the President’s Academic Excellence Initiative. Please get to know our new colleague below!

CENES: What excites you about coming to UBC and unceded Musqueam lands?

Tim Frandy: So much excites me about joining UBC. As a member of the Sámi American community, I’m thrilled to be joining an institution like UBC that has committed to deep collaboration with Indigenous communities in the difficult work of decolonization. I’m humbled to live and work on Musqueam lands, and I look forward to learning from them and other Coast Salish peoples. I’m excited to build upon my Sámi and Anishinaabe work, and produce Indigenous-centered work that is valuable to local communities as well. I couldn’t be happier being able to do work I’m passionate about, while living in one of the most beautiful places on the planet.

CENES: What aspects of Nordic Studies do you hope to introduce students to that they may not know about?

TF: I’m particularly excited to be able to develop Sámi, Greenlandic (Kalaallit, Inghuit, and Tunumiit), and other circumpolar content within our Nordic Studies curriculum. Looking at Nordic history from an Indigenous perspective has much to teach us about settler colonialism and the machinations of racism, about culturally-constructed concepts of environment and sustainability, and about how to build a future in which Indigenous people cannot merely exist but also thrive.

CENES: This position is part of a Climate Emergency initiative. What do you hope to contribute on this matter?

TF: Far too often, Indigenous people are limited to advisory or “seat at the table” roles within discussions on climate change and land use, while remaining excluded from any real decision-making power. Indigenous people need to be front and center in conversations about climate change. I hope to use my position to advocate for the efficacy and brilliance of traditional Indigenous stewardship, and to demonstrate the necessity of returning lands to Indigenous communities to address climate change.

CENES: What aspects of Indigenous scholarship do you hope to strengthen here at UBC?

TF: Right now, I’m interested in the way that traditional ecological knowledge is embodied in stories, in behavior, and in expressive culture. What can this knowledge teach us as we address the challenges of today? How can we cultivate traditional epistemologies in ways that allow them to breathe and grow? How can we craft scholarship that is itself within the traditions of Indigenous discourses, rhetorics, and logics? While I have no simple answers, I’m looking to grow my work in these directions.

CENES: What else would you like folks in the UBC community to know about you?

TF: I spent much of the last decade working with Anishinaabe communities, building cultural curricula in the public schools. Working with master artist Mino-Giizhig (Wayne Valliere), we built several birchbark canoes, brought back traditional games to the community, and brought young people into sugar and rice camps. The effect on the young people in the community has been utterly transformative because we weren’t just teaching the culture, but rather we were teaching culturally. We need to realize how central culture is in education, in health care, in environmental management, if we want to build better systems. That’s what my work is all about.

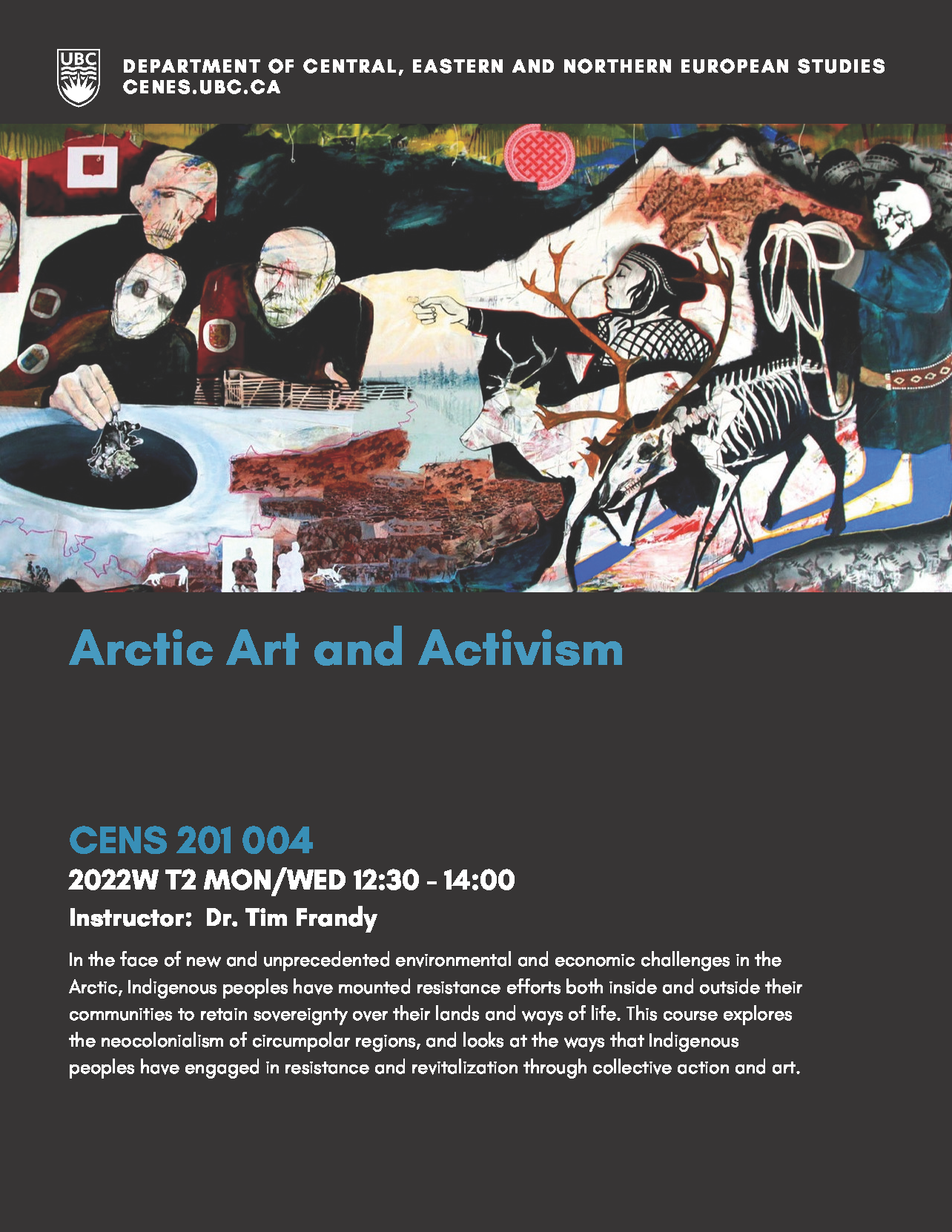

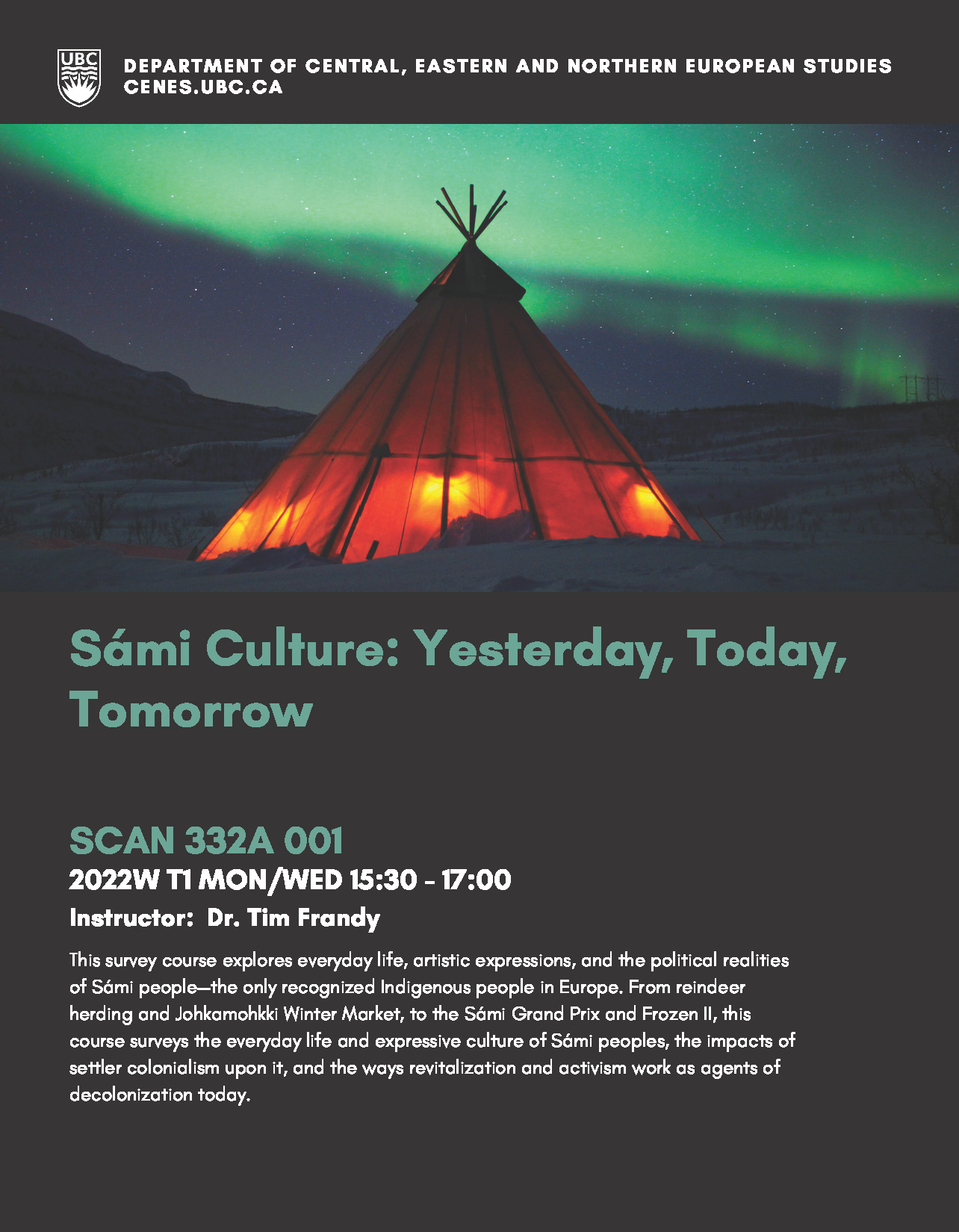

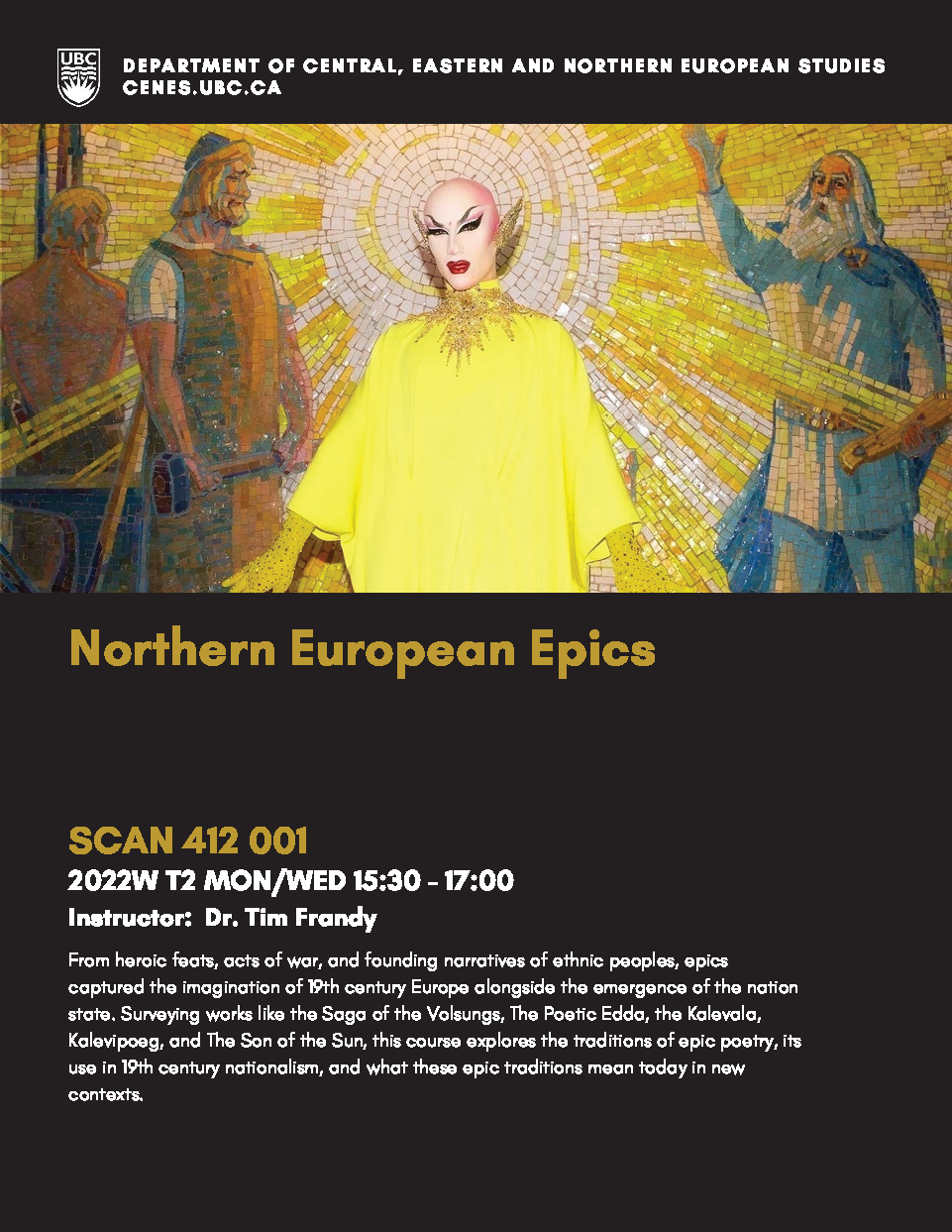

Interested in taking a course with Dr. Frandy? Check out their Winter 2022 courses below!