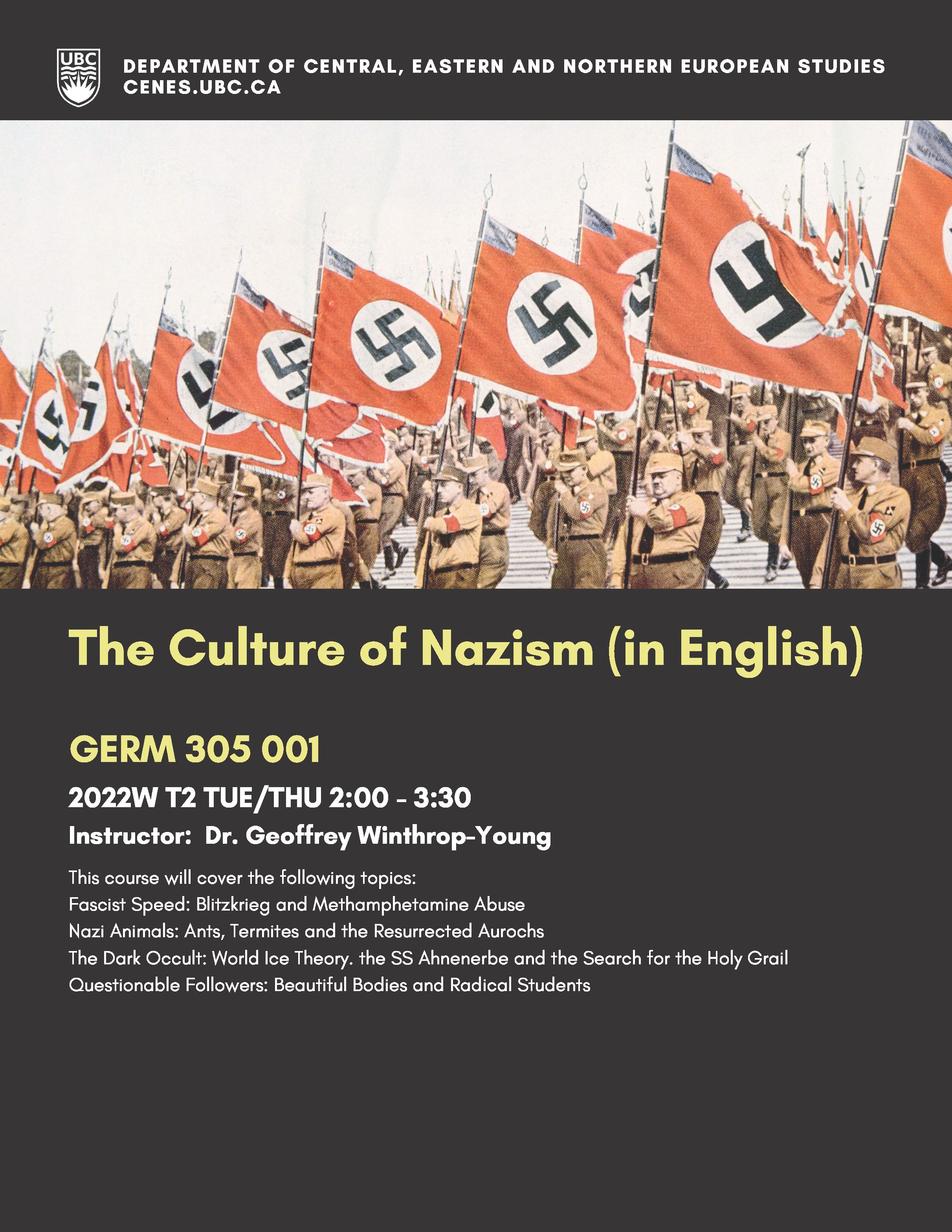

The Department of Central, Eastern and Northern European Studies (CENES) is thrilled to host an exciting array of courses in Winter 2022-23. Among these is GERM 305 001: The Culture of Nazism (in English), taught by Dr. Geoffrey Winthrop-Young, a three-credit course that explores selected features of the Third Reich, including methamphetamine abuse, attempts at species resurrection, university politics, and occultism.

CENES: What is the main focus of the course?

Geoffrey Winthrop-Young: The Winter 22/23 iteration focuses on four topics. First, the civilian and military (ab)use of the methamphetamine Pervitin — which serves to introduce the larger question how the Third Reich viewed health, bodies and Leistung (that is, performance and achievement). Second, the construction of the autobahn and the attempt to back-breed the extinct aurochs — which allows for a more general discussion of Nazi ecology and neocolonial rewilding projects. Third, some of the questionable esoteric, fringe or crackpot “scientific” theories and projects like World Ice Theory, Atlantis as the Aryan homeland, expeditions to Tibet, or the revamped search for the Holy Grail– all of which provide a back entry into the troubled relationship between science, society and academia during the Third Reich (and not only then). And fourth, universities and students–which allows for a general view of education and the way in which Nazism exploited and intensified generational divides for political purposes.

CENES: What gave you the idea to design this course in such a way?

GWY: If professional page number crunchers are to be trusted, the Third Reich is now the most written about epoch in world history (and Adolf Hitler the most written about person). Nobody can keep up with the scholarship; and you cannot ask students to plow through fifteen cubic meters of research before coming to class. I therefore went in search of lesser traveled roads that offered revealing backdoor entries into what the system was about.

CENES: What part of the course do you look forward to most?

GWY: In my experience, some topics raise in-class volume and temperature. For instance, talking about Nazi zoos and the autobahn, or the way in which the autobahn turns Germany into one big zoo. Ruin value theory is another favourite — how do we construct buildings so that a few thousand years from now they will be as impressive as Egyptian pyramids? World Ice Theory is a piece of comic relief; it’s the dumbest thing students will come across in four years at university–almost as dumb as some of the stuff you see on the news these days. But I look forward to species resurrection most because it is both so baffling and topical. On the one hand, the harebrained scheme to breed select domesticated cattle back into their feral ancestor, the fearsome aurochs, which will then be released somewhere in the East to help recreate a racially invigorating habitat. How familiar is that? How close it is to more contemporary projects to employ CRISPR and cloning to resurrect mammoths in order to recreate ecologically invigorating pleistocene habitats?

CENES: What is most difficult for students?

GWY: The most difficult element is also the most important. Nazi propaganda, though never as successful as it is made out to be, was nonetheless rather effective at projecting social and ideological unity. The former has come under intense scrutiny, but the latter remains less challenged, in part because it is so convenient to dismiss Nazism as a tawdry, crude, and dumb pseudo-theory. What I suggest to students is that there never was a proper, singular, clearly formulated Nazi ideology. Instead, there were (to use an ugly plural for an ugly business) National Socialisms, both across various countries and within Germany. Students have to dive into a pressurized compound of divisive and competing ideas, some of which, unfortunately, are highly extractable and connective — and that is what (once again) makes the ideology so dangerous.